Once again, this article was meant to be ready for the first day of Taurus—three days ago. But thanks to a welcome abundance of work, it's arriving just a little behind schedule. That said, the timing remains meaningful: we've only just crossed the threshold into the month of Taurus, and the lessons explored here are just beginning to unfold. I hope you'll carry them with you through the coming weeks, and enjoy the full bloom of spring.

From The Kitchen to The Cosmos

A very happy first day of Taurus to all my subscribers. The first month of 2272 Psc brought many exciting new developments into my life. As we now venture into the second month of spring, I’m looking forward to the continued planting of new and promising seeds in my life, and to watching them grow and develop over the next year.

This first day of Taurus is also a special day for me because it marks my Dad’s solar return—or his “true” birthday—the day when the Sun occupies the same ecliptic coordinates it did at the moment of his birth.

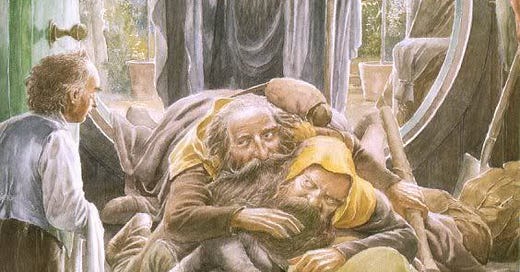

Like most dads, my Dad has been a monumental figure in my life—but all the more so in my case because, without obligation, he made the conscious choice to take on that role. My biological father had a very minimal, near-vacant role in my early childhood. But my Dad, Tim, came into my life when I was about three years old, fell in love with my mother, and immediately took on the responsibility of parenting me.

In fact, as I remember it, this was in no way simply a method to get into my mother’s good graces. He delighted in play and was eager to share his passions with me—many of which remain huge parts of my life today.

My Dad, a chef, brought me into his kitchen and put a knife in my hands, introducing me to a world of bright colors, bubbling, sizzling sounds, and, above all, incredible flavors and smells. He made every effort to take me to concerts of all his favorite bands—everything from Metallica to Kiss—and I fell in love with the spectacular performances and the emotional release of heavy, aggressive music.

He brought me on hikes and into the garden, even when I protested, and made sure I developed a deep and lasting bond with the natural world, quietly sharing his devotion to the Earth and all its living things.

(A typical Vermont view, like the ones my dad and I often saw on our hikes together)

Most importantly of all, he nurtured my imagination—taking me on journeys into fantastical worlds we built with Legos, immersing me in authors like Roald Dahl, Douglass Adams, and Tolkien, and sitting down with my mother and me once a week for our family movie night. It was the one night a week I got to watch anything on a screen, and I reveled in the chance to be transported into incredible worlds and epic adventures, as in films like Star Wars or The Princess Bride.

I think that for everyone who knows him, however, the most remarkable thing about my Dad is his incredible work ethic. It goes so far as to not even be considered a “work” ethic, because he simply found a way to build his life around his greatest passion: cooking.

He wakes up well before the sun every day, goes to his restaurant to open it up and start some prep work, returns home to his waking wife to cook her breakfast and lunch, cleans up, returns to work, cooks all day until the late afternoon, comes home, gardens, cleans some part of the house, cooks dinner and preps anything he needs for breakfast and lunch the next day, cleans up the kitchen again, and finally sits down to enjoy an episode of some show with his wife before going to bed.

He does all this while also managing his finances, enjoying his hobbies—like hiking, canoeing, reading, horseback riding, puzzling, building Lego sets, going to concerts, etc.—and occasionally working as a business consultant for other small business owners.

As a father myself now, I’m more in awe of him than ever before, and feel like I pale in comparison to the incredible achievements he made as a parent and provider. As I aspire to be for my own son, he remains my role model to this day.

Influence or Bias

Now, for my readers who are unfamiliar with traditional astrology, you might be wondering why I’m devoting so much of the introduction of this article to sharing about my Dad. To everyone else, however, the answer will be quite obvious.

My Dad was born on the first day of Taurus—on the “cusp,” a term referring to one born at the threshold of change between two adjacent signs of the zodiac, in this case Aries and Taurus. “Cuspers,” as they’re called, are said to embody strong characteristics of the sign under which they are born, but with a powerful influence from the other sign they cusp.

I began this article with such a lengthy description of my Dad because of how much he embodies the classic characteristics associated with Taurus, with some of that Aries influence highlighted as well—as I hope my readers will recall from my previous article on Aries.

But can the time of year someone is born really affect them in such a way, or do I simply choose to perceive my Dad through this lens and thereby confirm my own bias? I don’t have the answer to that, but I do believe that by exploring the historical evolution of the Taurus symbol, its connection to springtime themes, and its placement in the heavens as the constellation of the same name, we can begin to mold an understanding of how such an influence might be possible.

Finally, to help cement this concept in our psyche, we will explore Taurus through the lens of modern media—specifically, the most important book my Dad read to me when I was a child: J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

The Cave of Dreams

In the modern world, with our lifestyles shifted away from agriculture, our interests diverted into the devices in our hands, and our skies obscured by light pollution, most of us pay little attention to the night sky. Despite this, two constellations remain firmly rooted in the collective awareness—easily recognizable to many: Orion and Ursa Major.

While Ursa Major is often taught to American children because of the role it played in the history of slavery in the United States—as the Big Dipper, a prominent part of the constellation, was used to locate the North Star, a beacon of hope for enslaved people escaping north—both Ursa Major and Orion are made up of very bright stars arranged in ways that naturally inspire the human imagination. Across many cultures, these arrangements conjure up similar, familiar shapes.

If any one of us were to venture beyond our brightly lit cities, put away our devices, and spend our nights watching the skies over the course of a year, there are three other constellations that would likely stand out to us in the same way. Made up of exceptionally bright stars and arranged in strikingly recognizable patterns, these constellations are Scorpius, Leo, and Taurus.¹

As the astronomical record shows, these constellations have been firmly cemented in the collective awareness since at least the time of the development of agriculture—and likely even earlier. Taurus in particular, which often includes the iconic Pleiades, has been imagined as a bull, cow, or some kind of large horned bovid by many cultures across the world, even those with no known contact before the colonial era. This recurring image is likely due to the arrangement of the Hyades, an open star cluster and the closest such cluster to our solar system. From the point of view of Earth, these bright, young stars form a distinct “V” shape in the night sky, reminiscent of the horns of large bovids like cattle, bison, or buffalo.

(Taurus, as depicted in Stellarium)

Since the Spring Equinox first began to precede into the general range of this constellation around 4000 BC—marking the beginning of the last Age of Taurus—this symbol has carried strong associations with the fertility, vitality, and power of spring. These themes are similar to those of Aries, though Taurus boasts an even longer symbolic lineage. Its association with the season stretches back at least 6,000 years, before which the Sun would have occupied it during the final weeks of winter instead.

Cattle had already been domesticated by this time, likely as early as 10,000 BC—around the time of the last Age of Leo. The wild ancestors of the most common type of domesticated cattle—Taurine or Bos taurus—were the now-extinct aurochs, Bos primigenius. Humans and aurochs shared a long and storied history, stretching deep into the Paleolithic. Cave paintings and petroglyphs featuring these animals have been discovered across a vast range—from Spain to Russia to Turkey—testifying to their profound significance. Aurochs were clearly a vital resource for early humans, providing meat, hides, sinews, horns, and bones. Yet the frequency and reverence of their depiction also suggest a deep spiritual or symbolic importance.

If we are to speculate, we might imagine that the aurochs—offering such a wealth of life-sustaining resources—came to symbolize the abundant generosity of nature or the favor of the spirits. The act of hunting one may have carried its own sacred weight, as it surely involved danger and communal effort. Far from timid prey, aurochs were formidable animals—likely to defend their herd with great force—and their size and strength would have demanded courage and coordination from those who sought to bring them down. In this light, the aurochs may have stood as early symbols of vitality, strength, and fertility.

Incredibly, this animal might even represent the earliest known zodiacal symbol in the human imagination. One of the cave paintings at Lascaux, France, appears to depict a large bull-like figure alongside clusters of dots that some scholars interpret as the Pleiades and Orion’s Belt—grouped together much as they appear in the night sky. If this reading is correct, it could mark a moment when the constellation we now call Taurus first entered human symbolic consciousness, somewhere between 17,000 and 22,000 years ago—during what would have been the Ages of Scorpius or Sagittarius, according to the cycle of precession.

(The Aurochs of Lascaux, with groups of dots reminscent of the Hyades, Pleiades and Orion’s Belt)

Given the precession of the equinoxes, the constellation Taurus would have been most prominently visible just after sunset during mid to late spring and early summer at the estimated time of this cave’s creation. This seasonal timing may have coincided with important behavior in wild aurochs herds—such as calving, increased grazing, or migrations—potentially marking the beginning of the hunting season for our ancestors. If so, it is not difficult to imagine how the night sky, the rhythms of the earth, and the image of the great bull could have merged into a single, powerful symbol—one evoking themes of fertility, abundance, danger, and the life-death cycle. These associations may have endured in the collective memory for millennia, even as the precession of the equinox gradually shifted Taurus’s position along the ecliptic—persisting into the era when the more clearly documented zodiacal systems of the ancient world began to take shape.

(Taurus, Orion, and the Pleiades as they would have appeared around 20,000 years ago, to the artists of the cave paintings at Lascaux)

Milk, Muscle, and Majesty

For the ancient Mesopotamians, this constellation carried powerful springtime themes, especially in relation to the role of cattle in agriculture and settled life. Oxen, with their strength and endurance, were essential to early farming, as they could pull plows and transport heavy loads of grain and other agricultural goods. Just as important, however, was their ability to provide milk—a highly valuable and versatile food source, consumed fresh or processed into butter, cheese, and yogurt.

Because cows only produce milk while nursing their calves, and calving typically occurred in spring, this natural cycle further reinforced the constellation’s seasonal associations. The birth of calves around the time of the Sun’s rebirth at the spring equinox strengthened Taurus’s symbolism as a sign of fertility, abundance, and renewal—paralleling similar associations seen in Aries.

Taurus also inherited and expanded upon ideas already linked to earlier domesticated animals such as goats and sheep, particularly the symbolism of male virility, dominance, and patriarchal order that emerged in the early urban civilizations of the Fertile Crescent. But unlike caprids, bulls—with their size, strength, and imposing presence—came to represent a more commanding kind of power, one tied to kingship, divine authority, and elite privilege.

Only the wealthiest households or temples could afford to maintain large herds of cattle; most small-scale farmers may have owned just one or two. And because cattle were so valuable, their slaughter was likely rare and reserved for ritual or elite feasting. As a result, the consumption of beef may have been imbued with special meaning—further associating bulls with strength, wealth, and divine favor, as if their flesh itself conferred power upon those who consumed it.

The symbolic motifs associated with Taurus go even deeper than our relationship to the animals it represents or the seasonal themes tied to its visibility in the night sky. Like Taurus’ association with the boundary between winter and spring, this constellation appears to stand at the edge of another significant celestial threshold.

Heaven’s Hidden Gate

The Milky Way—our galaxy, coursing through the sky like an eternally flowing river—intersects the ecliptic at an angle of about 60 degrees in two places. The most prominent and easily visible intersection lies between Sagittarius and Scorpius. But under the right conditions—far from light pollution and near a new moon—we can glimpse the opposite intersection, where the Milky Way meets the ecliptic between Gemini and Taurus.

(The two places where the Milky Way intersects the ecliptic)

At some point in history, our ancestors realized that this shimmering, nebulous band formed a complete circle around the sky, dividing it into two halves, much like the ecliptic does—though at a different angle. As a result, the Milky Way also divides the ecliptic into two hemispheres. From Gemini to Scorpius lies the more luminous half, with zodiac constellations composed of many bright stars—eight of them brighter than magnitude 2.00—including Pollux (β Gem), Regulus (α Leo), Spica (α Vir), and Antares (α Sco). The other half, from Sagittarius to Taurus, consists of generally dimmer constellations, with only three stars brighter than magnitude 2.00: Elnath (β Tau), Aldebaran (α Tau), and Kaus Australis (ε Sgr).

These celestial patterns likely shaped ancient cosmologies and, in turn, the symbolic meaning of Taurus in a number of ways. For one, this division of the ecliptic may have inspired one of the most enduring symbolic motifs in human history: the duality of the known and the unknown, the familiar and the mysterious, the mundane and the extraordinary.

The half of the ecliptic from Gemini to Scorpius—with its brighter, more prominent stars—may have represented the familiar world. And near the heart of this luminous arc lie two of the most recognizable constellations, each carrying profound symbolic meaning: Leo and Virgo. Leo, the lion, with its entrenched association with masculinity, and Virgo, the virgin or maid, with its clear feminine connotations, together represent the sacred center of the known world—the divine masculine and feminine at the heart of cosmic order.

(A Stereographic projection of the night sky, centered on the half of the ecliptic between Taurus and Scorpius, showing Leo and Virgo at the center)

In contrast, the other half of the ecliptic—from Sagittarius to Taurus—is marked by dimmer stars and more abstract, less easily defined constellations. At its center, standing in opposition to Leo and Virgo, are Aquarius and Pisces. These two feature only two stars brighter than magnitude 3.00—α Aqr and β Aqr—and their obscure forms evoke mystery and transcendence. Throughout history, their symbolism has often resisted or defied traditional dualisms, existing instead in a space that is ineffable and unbound by polarity.

Additionally, since the Age of Taurus, the brighter half of the ecliptic has generally aligned with the summer months—a time of warmth and abundance—while the dimmer half has been associated with winter, a season of cold and scarcity.

The Milky Way, then, may be imagined as a great celestial wall, separating and safeguarding the known from the unknown. At the intersection near Scorpius and Sagittarius—where the Milky Way is brightest—this wall is thick and impenetrable. But at the opposite end, where it intersects near Taurus and Gemini, the Milky Way grows faint. There, the wall seems thinnest, most fragile.

And so it is at this vulnerable gateway that Taurus stands—guardian of the threshold. It holds back the terrors of the unknown from encroaching on the familiar, yet also guards the divine mysteries from mortal trespass. A sentinel of the boundary, Taurus protects both realms—preserving the sacred center within, and revering the ineffable beyond.

The Bull of Heaven

It is in this role as guardian that we can draw some of the earliest parallels to mythology. One of the oldest myths we have from the ancient Mesopotamians is the Epic of Gilgamesh, the story of a Mesopotamian king seeking immortality. The tale begins with Gilgamesh, the king of Uruk, portrayed as a powerful tyrant, abusing his authority to oppress his people out of boredom. The people cry out to the gods for relief, and the gods respond by creating Enkidu—a wild man capable of matching Gilgamesh in strength.

After Enkidu is tamed, he hears of Gilgamesh and sets out to confront him. Their battle, the first true challenge Gilgamesh has ever faced, ends in a draw, and the two men form a deep bond of mutual respect and friendship. United, they embark on a quest to slay the monster Humbaba, seeking fame and glory. When they return to Uruk, the goddess of love, Ishtar, is impressed by Gilgamesh and proposes that he become her consort. Gilgamesh refuses, mocking her by reciting the tragic fates of her former lovers. Infuriated, Ishtar pleads with her father, Anu—the god of the sky and king of the gods—to release Gulaana, the Bull of Heaven, to punish Gilgamesh.

Anu initially refuses, but when Ishtar threatens to unleash the dead upon the earth, he relents. In return, he demands that Ishtar ensure the people of Uruk are provisioned for the destruction the Bull will bring. When released, the Bull of Heaven devastates the land: he drains Uruk's water sources and opens a pit that kills hundreds. But Gilgamesh and Enkidu fight and slay the Bull, offering its heart to Shamash, the Sun god. Gilgamesh further insults Ishtar by hurling the Bull’s hindquarters at her. Humiliated, Ishtar ascends to heaven and demands divine retribution. The gods decree that Enkidu must die. After a slow and agonizing death, he does—and Gilgamesh, shattered by grief, resolves to overcome death itself and attain immortality.

(Gilgamesh slaying the Bull of Heaven, ancient Mesopotamian terracotta relief)

In this myth, we see clear reflections of the themes tied to Taurus—particularly in its role as a celestial guardian and a boundary between realms. Gulaana is an unmistakable reference to Taurus; in the MUL.APIN, the name of this constellation is Mul Gu-An-na (𒀯𒄞𒀭𒈾), literally meaning “The Bull of Heaven.” Here, Taurus appears not only as a divine agent avenging Ishtar's wounded pride but as a force that bars mortal access to the divine. The Bull of Heaven stands between Gilgamesh and his aspiration to transcend human limits, to become like the gods. His arrogance—abusing his power as king, slaying Humbaba for glory, scorning a goddess—marks him as one who seeks to overthrow the natural order. The Bull of Heaven is sent to humble him. Though Gilgamesh survives, the cost is immense: Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh is left to confront the terrifying finality of death, unable to escape it despite all his efforts.

We can also see seasonal resonance here: Taurus, whose rising heralds the spring, marked the beginning of the dry season in ancient Mesopotamia. Just as the Bull of Heaven drinks the waters of Uruk, parching the land, so too does spring mark the end of the nourishing floods and the beginning of arid months. Additionally, the myth embodies other Taurus-linked motifs: the Bull’s connection to royal power as an emissary of Anu, its ties to fertility through Ishtar, and the sacred reverence owed to cattle—so deep that slaying the Bull becomes an offense that demands a life in return.

Taken together, the myth of the Bull of Heaven reinforces Taurus’s role as both protector and threshold: a creature that defends the natural order from the hubris of man, standing watch at the edge of mortality and divinity. But it also reflects the deeper, ancient roots of Taurus as a symbol that shaped human consciousness long before this story was first carved into clay. From the Paleolithic reverence for wild bulls to the Neolithic domestication of cattle, Taurus has been bound to ideas of strength, fertility, and abundance—the lifeblood of survival and community. As agriculture transformed the human relationship to the land, so too did the bull come to embody stability, nourishment, and the order of kingship—power rooted in provision.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Bull of Heaven carries all of these associations: it is both divine and destructive, a sacred being tied to fertility through Ishtar, to royalty through Anu, and to cosmic order through the stars. Its slaying is not just a mythic feat—it is a symbolic violation of the old laws that had guided humanity for millennia. And so, as Taurus once stood at the center of early seasonal rites and agricultural rhythms, it stands here again, at the threshold of civilization’s oldest epic, reminding us that power without humility—abundance without reverence—comes at a cost.

The Cosmic Cow

Many similar themes also appear in the myths and iconography of the ancient Egyptian goddess Hathor. While never explicitly linked to the constellation Taurus, many scholars have argued that there is sufficient reason to believe that Hathor was somehow related to Taurus—at the very least, as a result of cultural exchange between ancient Egypt and ancient Mesopotamia. Hathor was a sky and sun goddess, commonly depicted as a cow or as a woman wearing a headdress with large cow horns. She was often referred to as a mistress of the sky or stars, and was believed to reside there with her consorts Ra or Horus, themselves also sky and solar gods.

Hathor’s role, however, was as a cosmic cow-mother goddess who birthed the Sun and placed it between her horns. This could, of course, be a reference to the placement of the Sun on the spring equinox in the area often depicted as the horns of the constellation Taurus during the period of predynastic Egypt (before c. 1270 Tau, the Age of Taurus, or 3100 BC), and generally within or close to that area all the way through the Early Dynastic Period (c. 1270–1686 Tau, or c. 3100–2686 BC) and the Old Kingdom (1686–2191 Tau, or 2686–2181 BC).

(The Sun, positioned around the horns of Taurus on 01/♈︎/1270 Tau, or 15/04/3100 BC [left], and a common depiction of Hathor, with the Sun in between her horns [right])

Throughout this vast period of history, artifacts from Egypt clearly show cows, women with arms raised above their heads reminiscent of horns, or Hathor herself—all often depicted with the Sun or other stars between the horns or surrounding them. When we consider the placement of the Sun at the spring equinox in Taurus, marking the Age of Taurus, the depiction of this deity as female—as a goddess—is quite easily understood as the cow birthing the Sun, since the spring equinox represents the rebirth of the solar cycle.

As a mother goddess, Hathor was associated with abundance, fertility, sexuality, and maternal care. The cow itself is easily understood as representing these principles when we consider how prolifically the species reproduces, and how caring they are toward their young—providing nourishing milk and protecting them in herds. Additionally, when we look at what cattle provided for humans in agricultural practices—in the form of labor, fertilizer, and as a source of food in themselves—we might propose that the exponential increase in abundant food sources and the development of civilization at this time could have been understood through the symbol of the bull or cow, as the Sun resided in this constellation during the spring equinox.

In ancient Mesopotamia, Ishtar represented many of these qualities, and we have already seen her connection to the Bull of Heaven in the Epic of Gilgamesh. But the ancient Egyptians also saw Hathor as embodying the powerful, vengeful spirit of the gods—akin to the Bull of Heaven. The Sun in ancient Egypt was known as the Eye of Ra, and as a sun goddess, Hathor was often equated with the Eye.

In one myth, Ra becomes furious with humanity for plotting to rebel against him, and he sends Hathor on a rampage to punish them. Her destruction, however, gets out of control, and Ra must stop her. He does this by getting her drunk, at which point she returns to her more pacified state—maternal and sexual.

A dualistic femininity is represented in Hathor, who can be tender, loving, and caring—or fierce, vengeful, and wrathful—similar to Ishtar and the Bull of Heaven, or to the males and females of the bovine species: cows and bulls. We might further connect this to the developments of civilization at this time, which provided incredible amounts of food and, therefore, greater specialization of labor that resulted in abundance in all aspects of society—abundance that could, at the same time, be harshly and cruelly ripped away by natural disaster or war. This terrifying existential dynamic had never been experienced within the simpler contexts of hunter-gatherer or even Neolithic farming societies.

A clear connection between Taurus and the material world seems to have emerged during this period, likely informing many of the symbolic meanings associated with the sign as astrology continued to develop.

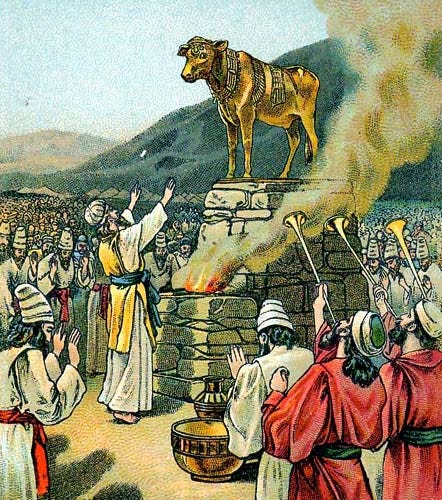

The Golden Calf

This symbolic understanding of the cow as related to the material world may also help explain the Biblical narrative of the Golden Calf in Exodus. In this story, after Moses has led the Hebrews out of Egypt and across the Red Sea, they stop at Mount Sinai, where Moses climbs the mountain to commune with God and receive the Ten Commandments. He remains there for forty days, during which time the Hebrews grow restless and fearful that Moses—and God—have abandoned them in the desert.

They go to Moses’ brother, Aaron, and demand that he give them a “god.” Attempting to placate and stall them, Aaron gathers up the Hebrews’ gold, melts it down, and casts it into the shape of a calf. He then tells them that this calf is God and builds an altar before it for the Hebrews to worship.

God informs Moses of what is happening and threatens to destroy the Hebrews, but Moses pleads for them, and God relents. When Moses descends, carrying the Ten Commandments, he becomes enraged at the sight of the people worshipping the golden calf and enacts a symbolic punishment: he grinds the calf into powder, mixes it into water, and forces the worshippers to drink it.

(The Hebrews worshipping the Golden Calf, illustration from a Bible card published in 1901 by the Providence Lithograph Company)

We can clearly sympathize with the Hebrews in this story—feeling abandoned and lost in the desert, and turning to a symbol of material abundance and renewal in the hopes of such favors being bestowed upon them. Moses, however, as the newly appointed shepherd of the Hebrews, would naturally be infuriated by this turn of events. He had led his people out of Egypt—a land of material abundance—with the promise that, despite hardship and suffering, they would be free and under the care of God.

This moment represents the potential shadow of the Taurine motif: attachment to the material, idolization of comfort, and fear of the unknown. Once again, we might recall the Bull of Heaven, sent to punish Gilgamesh for his own obsession with mundane power and fame at the expense of humility and reverence for what is sacred.

We can also understand this story through the lens of the precession of the equinox. When we examine the general features of Egypt as described in Exodus, they seem to align with the New Kingdom period. Assuming a semi-historical Exodus occurred, the Pharaoh in this story could very well be one of the New Kingdom rulers, such as Thutmose III (196–252 Ari, the Age of Aries, or 1481–1425 BC) or Ramesses II (c. 374–464 Ari, or 1303–1213 BC).

Additionally, 1 Kings 6:1 states that the construction of Solomon's Temple began 480 years after the events of Exodus. Most historians agree that King Solomon reigned during the mid-10th century BC (early 8th century Ari), which would place the Exodus around 480 years earlier—aligning with the reigns of Thutmose III or Ramesses II. As these dates suggest, the story falls within the Age of Aries, when the precession of the equinox shifted the Sun’s position at the spring equinox into the constellation of Aries.

We might interpret this narrative, then, as a symbolic expression of the Hebrews’ desire to return to the old ways—represented by Egypt and the golden calf, the Age of Taurus—which they were now being led away from by an Arian figure, the shepherd Moses, into the new Age of Aries. This new age emphasizes not the material needs of society, but the spiritual need for a guiding shepherd in times of transformation.

The Ten Commandments are that guide—symbols of a new moral order meant to lead humanity through the trials of transformation. That Moses smashes them at the feet of the golden calf underscores the violence and resistance often inherent in great shifts of consciousness. In this, the story becomes more than a myth—it mirrors the universal human tension between clinging to the familiar comforts of the past (Taurus) and embracing the uncertain path of spiritual and historical renewal (Aries).

Lovers, Labors, and Labyrinths

This cyclical process of renewal would play out again about 1,000 years later, as the Sun’s position on the spring equinox neared the end of its journey through the constellation Aries and crept closer to Pisces. Throughout this period—the Age of Aries—the Greeks adopted the Mesopotamian astronomical system and incorporated it into their own cosmology, eventually creating the tropical signs of the zodiac and integrating those symbols into their stories and myths.

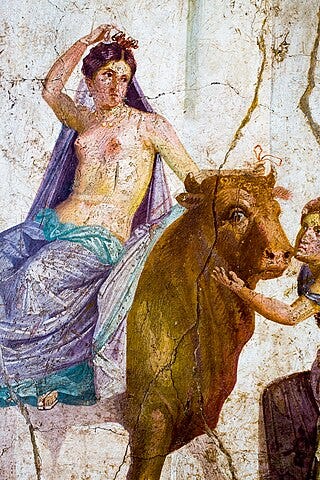

The story that contains the clearest reference to the constellation Taurus is the story of Europa. In this tale, Zeus, the king of the gods, sees Europa, the daughter of a cowherd, and becomes enamored with her beauty. Ever fearful of his wife Hera’s dangerous jealousy, Zeus transforms himself into a beautiful white bull and mingles with Europa’s father’s herd.

Europa, gathering flowers in the pastures, sees the white bull and, drawn to its divine allure, approaches it to caress it. Coming under Zeus’ spell, she climbs onto the bull’s back—at which point Zeus bolts to the sea, jumps into the water, and carries Europa across it. He brings her to the island of Crete, where he transforms back into his human-like form and seduces her.

(Europa and Zeus as a bull, fresco from Pompeii)

As a result of this experience, Europa becomes the first queen of Crete and is given a series of gifts from Zeus, including a beautiful necklace, a man made of bronze who protects Crete from pirates and invaders, the hunting dog Laelaps who always catches his prey, and an enchanted javelin that never misses its mark. To commemorate the entire experience, Zeus casts the shape of the bull into the stars, creating the constellation Taurus.

Another story often connected to Taurus is the tale of Io. Once again, Zeus is lusting after someone other than his wife. Io is transformed into a cow—either by Zeus to protect her from Hera, or by Hera to punish Zeus for his infidelity. Various versions detail the contest between Hera and Zeus over Io. Ultimately, Hera’s attempts to prevent Zeus from being with Io fail, and so she sends a gadfly to perpetually bite Io, forcing her to flee across the world.

She crosses the passage connecting the Black Sea to the Propontis (Sea of Marmara), which afterward becomes known as the Bosphorus—meaning “cattle passage.” On her flight, Io meets Prometheus, who has been eternally punished for stealing fire from the gods and giving it to humanity. Prometheus offers Io hope in her despair, telling her she will be the ancestor of the greatest Greek heroes. Finally, Io makes it to Egypt, where Zeus restores her to human form and fathers two children by her.

(Juno Discovering Jupiter with Io, by Pieter Lastman)

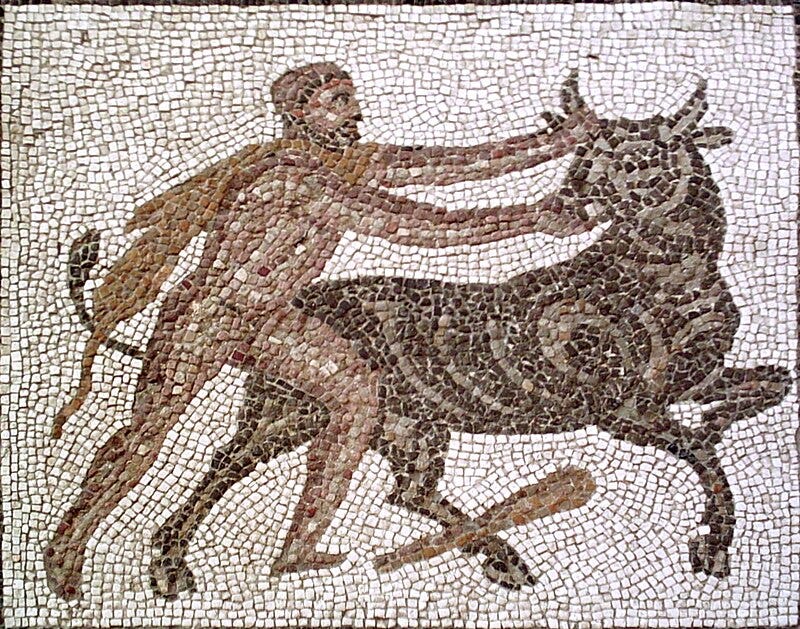

One final myth possibly connected to Taurus is the story of the Cretan Bull. King Minos of Crete, seeking a sign of the legitimacy of his rule, prays to Poseidon to send him a white bull. Poseidon does so, with the understanding that Minos will sacrifice the bull upon receiving it. But Minos prizes the splendid bull too greatly and, instead of sacrificing it, decides to keep it.

Poseidon, infuriated, punishes Minos by having Aphrodite curse Minos’ wife, Pasiphaë, with an insatiable lust for the bull. The result is Pasiphaë giving birth to the Minotaur, the half-man, half-bull monster that dwells in Minos’ labyrinth. Poseidon then fills the bull with rage, and it goes on a rampage across Crete.

Later, Heracles is given the task of capturing this bull by King Eurystheus of Tiryns as one of his labors. Minos gladly grants Heracles permission to do so, and after capturing the bull, Heracles brings it back to Tiryns, where it is kept until it escapes, wandering into Marathon. Finally, Theseus—the hero who later faces off against the Minotaur in the labyrinth—captures the bull and sacrifices it in Athens.

(Hercules capturing the Cretan Bull. Detail of The Twelve Labours Roman mosaic from Llíria)

Some of the most striking Taurian themes seemingly contained within these stories relate, perhaps, to the transmission of this symbol from the Near East to the Greeks. Both the stories of Europa and Io involve journeys across the sea, particularly emphasizing the connection between East and West. When Zeus, in the form of a bull, escorts Europa across the sea, he brings her to Crete—the home of one of the world’s oldest civilizations, Ancient Minoa—which flourished during the latter half of the last Age of Taurus and through the early centuries of the last Age of Aries (c. 1270 Tau – c. 570 Ari, or c. 3100 – c. 1100 BC).

The Minoans, through growing connections with the Ancient Greeks, had a significant impact on the development of Greek civilization and can be thought of as one of its progenitors. Additionally, Crete would have been an important hub for sea-based trade within the Mediterranean, and thereby a key point in the transmission of Near Eastern ideas—like the zodiac—to the Ancient Greeks. In this sense, Zeus placing the bull in the sky as the constellation Taurus can be thought of as a history, encoded in myth, of the transfer of this symbol from the Near East, through Crete, and finally to Greece.

The story of the Cretan Bull also highlights the importance of Crete, albeit in the opposite direction—from Crete to mainland Greece. Similarly, the story of Io fleeing from mainland Greece to Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), and crossing the straits that would thereafter be named for her—the Bosphorus—also references this movement between East and West. This bears a striking resemblance to the story of the Golden Ram, Phrixus, and Helle, as the straits on the other end of the passage—connecting the Sea of Marmara to the Aegean Sea—were named for Helle after she fell from the Golden Ram during their crossing.

In addition, Io ends her journey in Egypt, another important member of the Mediterranean community, which likely played a role in the transmission of ideas among these civilizations. Beyond the practical, physical movement of these ideas, the recurring theme of the bull or cow traveling between East and West can also symbolize the Sun’s placement in the constellation Taurus on the Spring Equinox during the Age of Taurus. In this view, the East—the location of the rising Sun—acts as a symbol of rebirth (like the Spring Equinox), while the West—the location of the setting Sun—serves as a symbol of death.

Beyond this, these stories contain symbolic motifs that echo the story of the Bull of Heaven or the character of Hathor. The most obvious theme is that of sexuality and fertility. Zeus’ central motivation in both the Europa and Io myths is lust, and his union with Io results in a lineage that produces nearly every great Greek hero. Similar to Ishtar’s role in the story of the Bull of Heaven in Gilgamesh, or Hathor’s role in Egyptian mythology, the bull or cow appears as a symbol strongly associated with fertility and the abundance it implies.

We also see this theme in the story of the Cretan Bull, though the trope is inverted. The union of the bull and Pasiphaë results in the birth of the Minotaur—a monster who, in the story of Theseus, consumes the youth of Athens, rendering them symbolically infertile. The Cretan Bull also carries Taurian themes of kingship and power, as it is sent by Poseidon to Minos as a divine sign legitimizing his rule.

Throughout all these stories, we encounter powerful themes: the lure of the material world, the tension between sex and power, the meeting point of the divine and the mundane, and the dangerous forces of nature that punish those who fail to revere the sacred. These are all themes we might associate with Taurus’ placement at the frontier of the Milky Way boundary.

The Refusal of The Call

When the Greeks devised their own tropical system of the zodiac, Taurus was designated for the ecliptic coordinates 30° to 60°—the area of the sky the Sun occupies during the middle third of spring. This roughly corresponded to the location of the constellation Taurus at the time this system was created, during the final stretch of the last Age of Aries, in the final centuries BC. But aside from the astronomical data of that time, we can understand the association of the Taurian symbol with the middle of spring in a number of ways.

First, there is the power and authority associated with the bull. Placing it in the center of the season aligns with this thematically, as the center of each season is thought of as “fixed” in traditional astrology—meaning cemented in place, firmly rooted in its themes, and most emblematic of the season’s essence. Like a king is to a kingdom, it is the stable core of the season. When we also consider the fertility, sexuality, and abundance associated with Taurus, we can see the connection to this time in spring as well. In much of the northern hemisphere, this is the time of spring rains, returning greenery, and flowering—natural phenomena that inspire themes of fertility and abundance.

We can also understand the Taurian themes throughout history through the lens of the monomyth. If Aries was the Call to Adventure—when the hero is inspired to leave the comfort and safety of the familiar, stagnant, and oppressive world they occupy—then Taurus is the Refusal of the Call. In this stage of the journey, the hero resists the urge to leave their familiar world. This can be for a number of reasons, such as a sense of duty, fear, or feelings of inadequacy, but it can also result from external forces holding them at bay. The most important feature of this stage, however, is that the hero momentarily rejects the unknown or mysterious in favor of the comfort, safety, and pleasures of their stagnant existence within their familiar world.

We can connect this to the Taurian myths in a number of ways. First, Gilgamesh literally refuses a call from Ishtar to be her lover because he does not wish to suffer the same consequences as her other lovers. This is quite the rejection, because despite the dangers involved, he is turning down the opportunity to experience the love of a goddess—something that definitely transcends anything he could experience in the mortal world. The bull in this story acts as the element that forces Gilgamesh beyond what is familiar by leading to Enkidu’s death and inspiring him to finally set off on his adventure to seek immortality.

In the story of Ra employing Hathor to punish humanity in their rebellion, we can also see the theme of a force oppressing a heroic instinct—here, the act of rebellion—and enforcing a continued maintenance of the established order. Both the stories of Europa and Io result in Zeus, the most powerful being in reality, stooping to the level of disguising himself and playing tricks in the pursuit of physical pleasure. Acting out of fear of retribution from his wife, these are actions that could certainly be compared to a heroic figure rejecting their higher calling and, in their insecurity, hiding amid tangible, familiar pleasures.

And finally, Minos himself represents this Refusal of the Call in his refusal to sacrifice the bull to Poseidon in gratitude. He is so fixated on the abundance the bull symbolizes that he cannot let it go, and as a result, he is cursed with his stepson, the Minotaur—a symbol of his own lust for power—that he hides away in a labyrinth and sustains on the vitality of the young.

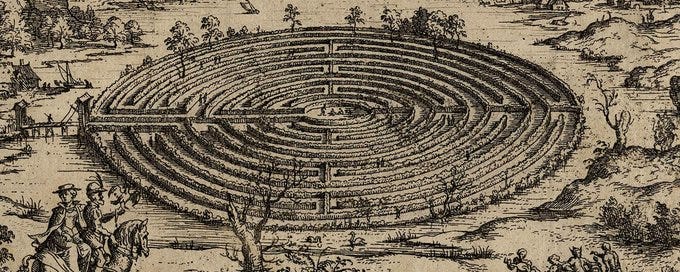

(A depiction of King Minos’ Labyrinth)

While most of these interpretations seem to paint the symbol of the bull or cow in a strongly negative light, it is important to recognize that the Refusal of the Call exists within the framework of the monomyth for a reason. The hero must see the beauty and wonder of the world they already occupy—even if it distracts them from their higher calling for a moment—because otherwise they would have nothing calling them back to that world once they have completed their journey. The Refusal of the Call can also be a symbol for recognizing the wonderful things that already exist around you, and the incredible luxuries they provide in your life—things you will certainly miss once they are gone.

Taurus Today

In modern astrology, Taurus is often described as strong, reliable, patient, practical, responsible, and stable—but also stubborn, materialistic, and inflexible. Those born under this sign are said to enjoy rich and pleasurable experiences: gardening, working with their hands, cooking and eating, listening to music, and indulging in high-quality goods. At the same time, they may shy away from complexity, emotional insecurity, or sudden change.

These traits make sense when we consider the symbolic lineage of Taurus and how its mythic motifs are rooted in celestial and seasonal realities. As archetypal themes, fertility and abundance provide the broader framework for Taurus’s earthly pleasures—food, nature, beauty, and sensuality. Meanwhile, the themes of power and rulership are closely linked to consistency, dependability, and a deep sense of responsibility.

Of course, there's no way to prove that the placement of celestial bodies in the degrees of Taurus directly causes someone to exhibit these traits—and indeed, that thesis may ultimately be wrong. But in the end, that isn’t the point. What matters is that these ideas speak to universal patterns drawn from our experiences in the natural world—both in the life cycles we witness on Earth and in the cosmic imagery that fills our skies.

We live within these rhythms. We are shaped by them. And whether consciously or not, we carry their motifs within us—some of us more than others.

Finding Taurus

It’s no wonder, then, that in a modern society which does little to teach us these symbols in any direct way, many people view the ideas associated with Taurus as arbitrary—or at the very least, archaic. And yet, Taurian motifs surround us in the world today, if we only know how to recognize them.

When I was a child, my dad read to me one of the most important books I’ve ever encountered: The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien. I remember the version he read vividly, not only for the story itself but for its stunning illustrations by the artist Alan Lee. As I listened to my dad’s voice narrating the tale, I would get lost in the artwork—its muted color palette of greys, pale yellows, greens, and blues; the intricate details that brought Tolkien’s language to life; the somber, stoic faces of the characters that deepened the otherworldly mood of the story.

(The cover of The Hobbit, illustrated by Alan Lee)

This was, at least as far as I can remember, my earliest foray into the world of fantasy, and I was completely enraptured by Tolkien’s magical realm of wizards, monsters, and human-like races. I even have a distinct memory of growing impatient with the pace of my dad’s reading—so I stole the book away and began reading it on my own.

The Hobbit holds a special place in my heart—not just as a beautiful story, but for the bond it helped forge between my dad and me. So imagine my delight, years later, when I began studying astrology and realized just how deeply saturated this story is with Taurus symbolism—especially since it was my dad, a Taurus, who first introduced it to me.

A Hole in The Ground

At its heart, The Hobbit is a tale of the enduring beauty of simple, grounded goodness—and how easily that goodness can be unsettled by fear, greed, or the lure of more. Its central figure, Bilbo Baggins, is a hobbit: a creature smaller than a man, about the size of a prepubescent child, with leathery, hairy feet that require no shoes. Hobbits live in elegantly carved holes in the earth, and spend their days farming, gardening, and partaking in the pleasures of good food, drink, and pipe-smoke.

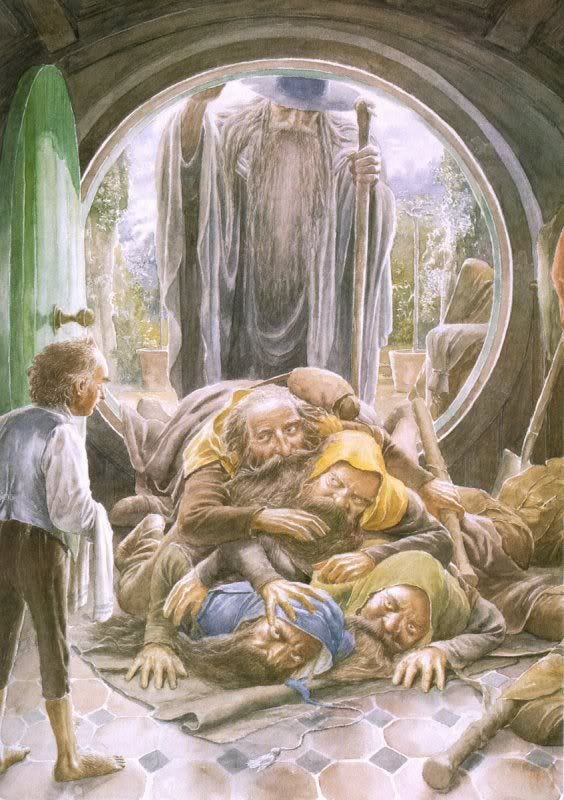

Bilbo, even among his kind, is well-off and content. He enjoys a life of cozy luxury—quiet, ordered, and rooted. But one day, the wandering wizard Gandalf arrives on his doorstep, and with a smile full of mischief, tricks him into hosting a company of thirteen dwarves for supper.

(The arrival of the dwarves, by Alan Lee)

The leader of this company is Thorin Oakenshield, heir to the lost dwarven kingdom of Erebor, which once lay deep within the Lonely Mountain. The rest of the company are his kin and loyal companions, determined to help Thorin reclaim his throne. Their kingdom, once a marvel of craftsmanship and wealth, fell when its treasure attracted the attention of a dragon. Smaug descended upon Erebor in fire and fury, laying waste to it, scattering its people, and nesting atop its golden hoard ever since.

Now, Thorin seeks to reclaim what was lost. Gandalf, sensing the turning of fate, wishes Bilbo to join the company as their burglar—hobbits, after all, are known for quiet feet and going unnoticed. Bilbo, unsurprisingly, resists. He wants no part in this dangerous errand, especially not with a group of raucous strangers who drink all his ale and sing in his dining room.

But when the dwarves mock the idea of a hobbit accompanying them, something in Bilbo hardens. Defiantly, he agrees to go—not out of wanderlust, but to prove a point.

From the very start, we are steeped in Taurian themes. Hobbits are, in many ways, a race of Taurus-folk: lovers of earth, beauty, comfort, food, and the quiet rituals of life. They live within the hills, their bare feet always in contact with the soil, their days filled with cultivation and repose. Thorin’s journey is not just a quest for justice or vengeance, but one driven by the lure of gold, echoing the Taurian mythos of material abundance and earthly power. And Bilbo’s initial hesitation—his refusal to leave the warmth of home—is a classic Campbellian Refusal of the Call. Only when his pride is pricked, and his sense of worth questioned, does he step out the door.

Not because he wants treasure. Not because he seeks glory. But because, like a bull protecting his herd, he cannot abide being underestimated.

Riddles in The Dark

As Bilbo, Gandalf, and the dwarves set off on their adventure, the dwarves remain skeptical of Bilbo’s usefulness. Their doubts appear to be confirmed early on when Bilbo blunders his first real task as a burglar. Sent ahead to steal from three trolls camped in the forest, Bilbo is promptly caught in the act, which leads to the capture of the entire company. The trolls argue over how best to cook them all, buying just enough time for Gandalf to arrive at dawn. He tricks the trolls into debating until the sun rises—turning them to stone. In the aftermath, the company finds a small horde of treasure among the trolls’ belongings, including a cache of elegant elven blades, which they take with them.

From there, they journey to Rivendell, where the lord of the elves, Elrond, helps them decipher secret runes on their map. These runes reveal a hidden entrance to the Lonely Mountain. Soon after, while camping in the treacherous Misty Mountains, the company is captured by goblins and brought deep underground to the goblin king. Gandalf arrives once more in a moment of crisis, killing the goblin king and clearing the way for their escape. But Bilbo is separated in the chaos, and tumbles down into the depths of the mountain.

Alone, and for the first time truly isolated from the others, Bilbo discovers a small, unmarked gold ring—seemingly ordinary, but possessed of the power to make him invisible. In the gloom, he encounters Gollum, a twisted and eerie creature who challenges him to a game of riddles. Bilbo wins—barely—and evades Gollum’s treachery with the aid of the ring, slipping away unseen and finding his way out of the mountain to rejoin the company. But danger follows quickly. The goblins pursue them on wolfback, trapping them in the trees and setting them alight. It is only through the intervention of great eagles that Bilbo and the dwarves are saved, flown to safety on the edge of the next chapter of their journey: the dark forest of Mirkwood.

(Bilbo in Gollum’s cave, by Alan Lee)

This section of the story is rich in Taurian motifs. The troll encounter, for example, centers around food—not just Bilbo’s attempt to steal it, but also the trolls’ gruesome appetite for the dwarves. Their obsession with how best to prepare their meal ironically buys the time that saves the company. The reward for this ordeal is treasure: gold and finely crafted weapons, hinting at the material payoff that often follows hardship. We can even imagine this scene as akin to Gilgamesh and Enkidu enjoying the spoils of their vanquishing the monster Humbaba, and ignoring the warnings of Ishtar, which brings upon them the ruin of the Bull of Heaven. In both tales, the conquest of monstrous, earthly forces is followed by the temptation of wealth and overconfidence—underscoring the Taurian tension between indulgence and consequence.

Bilbo’s experience in the Misty Mountains also echoes the Taurian mythos of King Midas, the labyrinth, and the Minotaur. Trapped in a maze of uncertainty beneath the mountains—frozen in place on his quest, terrified and alone—he is forced to reach within and find some inner strength to guide him. And it’s precisely here, in the darkness, that he discovers his greatest asset: the ring. More than that, he discovers his own resilience. The ring itself is a perfect Taurian symbol: unadorned yet beautiful, elegant in its simplicity, and enormously powerful. It offers a kind of material magic—something tangible, something real—that grants Bilbo a psychological foothold in the chaos. Where the Taurus archetype often hesitates in the face of uncertainty, clinging to the known and grounded, the ring gives Bilbo just enough of an edge to step forward with new courage.

And once again, when all seems lost, salvation comes not through strategy or strength, but through luck—or perhaps providence. The eagles arrive like celestial guardians, lifting Bilbo, Gandalf, and the dwarves out of danger and placing them safely on solid ground again. It’s as if Zeus himself is coming to rescue them, just as he finally relieves Io of Hera’s torment and ferries her to safety. Similar to Io, the Hebrews in the desert faced a test of faith in the wilderness—but where Io endures, holding to the promise of eventual deliverance, the Hebrews falter, turning instead to the golden calf. These parallel cattle symbols reflect the Taurian paradox: when Taurus draws upon its deep well of patience and endurance, it survives the chaos and receives divine reward. But when it succumbs to fear and craving, it regresses—missing the moment of grace that was already on its way.

Straying from the Path

The eagles gracefully leave the company at the home of Beorn, the skin-changer. Beorn is a magical being who can change his shape from bear to man. He is distrustful of strangers, but Gandalf’s clever diplomacy—and the fact that they are running from goblins, which Beorn hates—convinces him to accept them. They receive some much-needed food, comfort, and rest at Beorn’s, and when they leave, he gives them advice for the journey ahead, ponies to aid them, and supplies. But Gandalf also departs at this moment, just as they are about to enter Mirkwood—the largest forest in the world, full of terrifying dangers. Both Beorn and Gandalf warn Bilbo and the dwarves never to stray from the path through the forest.

Mirkwood has a constant, foreboding eeriness, and Bilbo and the dwarves begin to clash as they fall under the forest’s claustrophobic and dreamlike spell. The dwarves seem to quickly forget the warning about staying on the path. One of them, Bombur, falls into an enchanted river, falls asleep, and cannot be woken for many days. When he finally wakes, he remembers nothing. At night, the forest begins to feel malevolent—full of menacing noises in the pitch black, as the canopy of trees blocks out all moon and starlight.

At one point, when they can take the desperation of their situation no longer, they send Bilbo up to the top of a tall tree to see if he can spot the forest’s edge—but he can see nothing. One night, their wavering psyches crack as strange lights appear in the forest and dance around them. The lights seem to come from wood-elves having a celebration, but whenever they get close, the lights go out, leaving them in blackness. They begin to panic, and run amok in a mad frenzy, breaking off in different directions and getting separated.

Bilbo, determining that running around blind will do no good, sits down and dozes off. When he wakes, he discovers he is being tied up by a giant spider. He kills the spider, and after a search, finds the dwarves captured, tied up, and weakened by the poison of other giant spiders. He uses the invisibility of the ring to cause confusion among the spiders and frees the dwarves. He then dispatches several spiders that pursue them, naming his sword Sting in the process, and earning the undying praise and gratitude of the dwarves.

(The dwarves, captured by spiders, by Alan Lee)

But this victory is short-lived, as the next day they are captured by the wood-elves—Bilbo only narrowly escaping by using the magic ring. The dwarves, unwilling to explain why they are in Mirkwood to the king of the wood-elves, are thrown into the dungeon. Bilbo spends weeks hiding in the king’s palace, trying to figure out how to free them. He eventually comes up with a plan, and frees the dwarves by hiding them inside empty wine barrels that the elves drop down a trapdoor to the river, sending them floating downstream back to where they came from.

The departure of Gandalf at this point in their quest—just as they are about to face the terrors of Mirkwood—sends the company into a crisis that allows Bilbo to come forward and assume the role of their rescuer and leader. Like the constellation Taurus standing at the edge of the Milky Way, guarding the passage between the comfortable and familiar world and the unknown and mysterious one, Bilbo here becomes the only thing standing between the dwarves and the perils of Mirkwood.

He does this mainly through stealth, guile, and careful planning—traits we wouldn’t normally associate with Taurus, as they don’t seem connected to the actions of figures like Gilgamesh, Hathor, Minos, or any of the Taurian characters we’ve studied so far. However, the true power that Bilbo discovers here is not his stealth or wit—which have always been with him—but his determination. Bilbo is the only member of the company who does not fall victim to panic in Mirkwood, and the only one who seems to remember the advice that both Beorn and Gandalf gave them: to stick to the path.

It is this headstrong clarity that Bilbo is able to maintain—and this determined focus on the best way forward—that are his most Taurian traits here. This shows us the best of qualities that, in other stories—like Gilgamesh’s refusal to be distracted by Ishtar, or Minos’ stubborn refusal to give up the white bull—can sometimes lead to disaster, but here help pull the company through what is already a disaster.

A Merrier World

As Bilbo escorts the dwarves in their barrels away from disaster, they arrive at Lake Town—a village built upon the waters of the lake beneath the shadow of the Lonely Mountain. The townspeople become excited, believing the dwarves’ arrival to be the fulfillment of a prophecy about the dragon Smaug’s destruction. One man, however—Bard, the captain of the town archers—remains skeptical and wary of danger. Still, the Master of Lake Town supports their journey, providing supplies and boats to carry them upriver toward the mountain.

After a difficult ascent, the company reaches a hidden door in the side of the mountain. Once its secret is revealed, they send Bilbo in to investigate and retrieve a token. Inside, Bilbo discovers the vast hoard of treasure—and its immense, slumbering guardian: Smaug the dragon. Though Smaug senses Bilbo’s presence, he cannot see him, thanks to the invisibility of the magic ring. Bilbo uses flattery and riddles to distract the dragon while studying him for weaknesses. He spots a vulnerable place in Smaug’s scaled armor and slips away, taking a small trinket with him. This theft enrages the dragon. Believing the intruder to be from Lake Town, Smaug bursts from the mountain and flies off in a fury to destroy it.

The town is nearly obliterated, but a thrush who had overheard Bilbo’s words about Smaug’s weakness flies to Bard and tells him where to strike. Bard, with a well-placed arrow, brings the dragon down.

With the dragon slain, the dwarves believe victory is theirs. They enter Erebor and reclaim their ancestral kingdom and its treasure. Thorin, however, is searching for something more: the Arkenstone, a precious gem and heirloom of his house. But his obsession with it—and with the hoard itself—begins to trouble Bilbo. When Bilbo secretly finds the Arkenstone, he hides it instead of handing it over to Thorin.

Soon after, representatives from Lake Town, now led by Bard, arrive at Erebor, joined by the Wood-elves. They ask for a portion of the treasure—Bard to repair the destruction of Lake Town, and the elves to settle old debts. But Thorin refuses. Possessed by a growing greed, often called “dragon sickness,” he prepares for war and sends word to his cousin Dain to bring reinforcements.

Bilbo, unable to understand Thorin’s stubbornness, steals away in the night and gives the Arkenstone to Bard and the elves, hoping to avoid bloodshed. When Thorin learns of this, he is enraged. He banishes Bilbo and readies his forces.

Just before battle begins, Gandalf returns with dire news: an army of goblins is on its way. The dwarves, elves, and men unite to face this common threat. As the battle unfolds, Bilbo slips on the ring and vanishes from the fighting. The conflict is fierce, and it is only turned in their favor by the unexpected arrival of the eagles—and Beorn himself.

Bilbo, however, sees little of the battle. A falling rock strikes his head, and he loses consciousness.

When he awakes, the battle is over—and Thorin is dying. In his final moments, Thorin recognizes the error of his ways and speaks one of the most poignant lines of the tale: “If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.” He and Bilbo reconcile before Thorin passes.

(Thorin’s burial within the halls of Erebor, by Alan Lee)

Grieving his friend, Bilbo accepts only a small portion of the treasure, saying it is more than he could ever need. He returns home a wealthier hobbit—not merely in gold or magic trinkets, but in strength, wisdom, and character.

This final section of the book centers on the treasure and its profound impact on each central character. It reflects a key Taurian motif: an overwhelming abundance of wealth — like the milk of the cow or the bounty of the harvest — and how it shapes the fates of those who encounter it. The various responses to this treasure reveal the many faces of the Taurus archetype.

Smaug, and later Thorin, represent its shadow side. Both are consumed by possessiveness and greed, forsaking fellowship, compassion, even life itself, in the name of material gain. Like Gilgamesh turning away from sacred love in pursuit of eternal fame, or King Minos valuing the white bull over the favor of the gods, Smaug and Thorin place their hoard above the peace and prosperity of their fellow beings. Their paranoia over losing even a single coin blinds them to the damage their obsession causes. They cannot see that clinging to the treasure costs more than it gives — that the true value of their victory is lost when they value it above the lives and needs of others.

While the wood-elves’ demands for gold may seem politically motivated, the people of Lake Town are clearly justified in seeking a share. They endured the worst of Smaug’s wrath and played a direct role in his downfall. Without Bard’s arrow, there would be no kingdom for Thorin to reclaim. But Thorin, having finally gained the wealth and power he long dreamed of, views any concession as a betrayal — as though giving away part of the treasure is the same as losing all of it. This is the fury of the bull: unmeasured, unyielding, unable to distinguish between a real threat and a minor trespass. Whether faced with a single wolf or a legion of hunters, the bull responds with the same unrelenting force.

In contrast, Bilbo represents a more luminous expression of the Taurus archetype. Through his journey, he discovers that the true treasure is not the gold of Erebor, but the wisdom he has gained and the friendships he has formed. He sees clearly that peace and cooperation will always yield more than hoarded wealth. Rather than seek personal glory in battle, Bilbo takes quiet, decisive action — giving away the Arkenstone in hopes of avoiding war, even at the cost of Thorin’s trust. He acts not from a sense of heroism, but from care — for everyone, even those who once threatened him. It is a learned understanding of unity, of shared fate, of the preciousness of peace.

This stands in stark contrast to the Bilbo we met at the beginning of the story: a comfort-loving recluse in a quiet paradise, content to remain uninvolved in the world’s affairs. As a hobbit, he was raised to believe his kind were too small to make a difference. But through peril and camaraderie, through victories hard-won and fears overcome, Bilbo grows into a figure of quiet strength — one who dares to stand up for the good of all, even when it means standing alone.

Crucially, both the beginning and the end of Bilbo’s journey are valid expressions of Taurus. The Bilbo of Bag-End embodies the earthy contentment and domestic pleasure so familiar to this sign. But the Bilbo who emerges from Erebor is something more refined — like Hathor, the cow goddess of the sky, he nourishes those around him with something richer than gold. Like her celestial milk, his compassion and insight create an enduring abundance. He has not abandoned his love of food and cheer and song; rather, he has learned to carry that love beyond the borders of his home, and to share it with a wider world.

In the end, it is not the strength of the hoard — or the herd — that defines a Taurus, or any being, but what one chooses to do with abundance: to hoard it in fear, or to share it in love. This is the lesson Tolkien tries to share with us in The Hobbit, and it is the lesson echoed in Taurus figures throughout the history of this archetype, across cosmology and myth. It is what Gilgamesh must learn through the loss of Enkidu, and what Minos must confront when he suffers the consequences of keeping the white bull. The symbol of the bull — which once marked the Sun’s position at the Spring Equinox during the dawn of civilization — reflects the fertility and prosperity these early societies could generate, yet it comes with a warning. Like Zeus lusting after Europa and Io, the allure of such power is undeniably strong, and all of us must face it at some point in our lives. If we do not revere that power, we can become like the Hebrews worshipping the golden calf — idolizing the mundane, neglecting the true source of life’s richness, and hoarding in fear. Or we can be like Bilbo, recognizing that the strength of abundance lies not in how it shields us from perceived danger, but in how it binds us together in shared love, simple joys, and the making of a merrier world.

The Earth We Share

My dad — the chef, the parent, the lover of nature — was the first to read The Hobbit to me when I was a child. In so many ways, he was the perfect person to pass on the Taurian spirit: his love of rich flavors, playful imagination, and his deep appreciation for beauty and growth shaped my world in ways I will always treasure. He showed me how life can be savored through the material richness it offers — the warmth of a meal, the quiet of a garden, the peace of a well-loved home.

But like the Taurus archetype itself, he also had his shadow side. At times, he could be overly protective of the sanctity of home and routine, resisting and sometimes lashing out at even the smallest disruptions. And from my perspective, it seemed his marriage to my mother began to unravel when his need for structure clashed with her desire for freedom and spontaneity.

Of course, I know that both my parents could tell that story with far more nuance — and that my view of it may be shaped by my own symbolic lens, my own need to make meaning through archetypes and stars. But in the end, that doesn’t diminish the truth of what I’ve come to understand. I’m not reducing my father to the Taurus archetype to excuse or criticize him, nor to place him on a pedestal. I’m honoring the complex, deeply human person he is — and using the symbol as a mirror to understand both him and the broader pattern it represents.

Whether in the flowers and rains of mid-spring, the stars overhead, or in the quiet choices we make each day, Taurus calls us to tend the material world with care — to build something lasting, something nourishing. It teaches us that true abundance isn’t about possession, but provision. That the joy of life lies not just in what we gather, but in how we share it. And that our greatest treasures are the ones we create in connection with others — with our herds, our homes, and the Earth we share.

¹ Excluding, of course, the far northern or southern portions of the sky, which may be obscured depending on one’s latitude.